The North Face is Empowering These London Artists To Explore Their Creative Peaks

Sponsored StoryIt sounds like the set up to an outlandish story that could only happen in 2019: An artist famous on the ‘gram for painting boys’ nails and a Black, queer transgender spoken word poet walk into a nondescript apartment block in London. But this is far from fiction.

On any other day, they’d be two creatives among the city’s nearly nine million residents but today, Jess and Kai are in this nondescript apartment block for a reason. Not only are they at the forefront of their artistry, but they’re also experts at climbing mountains — no, not the snow-capped peaks of Mount Everest or Mount Something-Or-Other. They’re climbing their own personal mountains; something that’s caught the well-weathered eyes of The North Face.

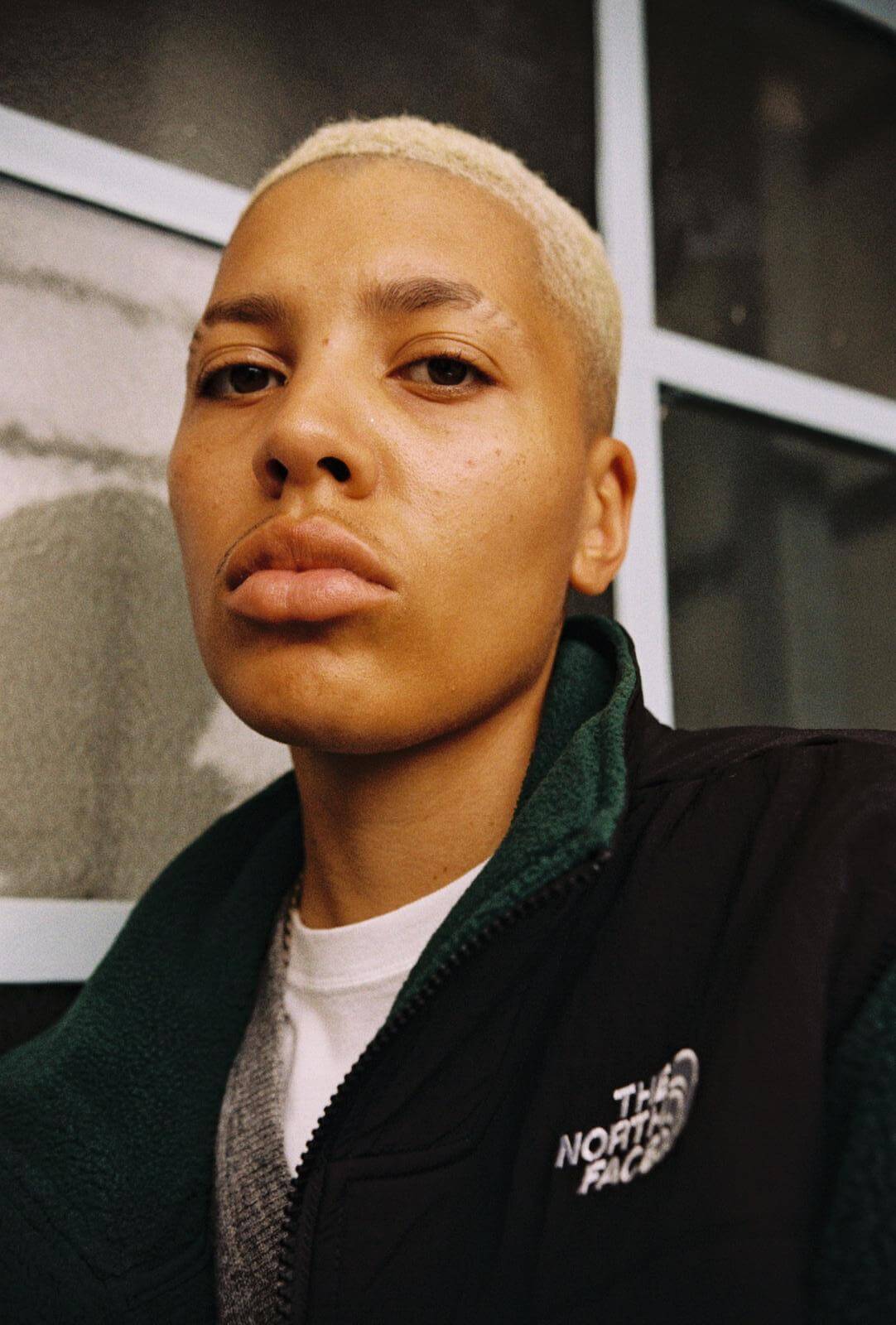

For the North American sporting goods brand, their name comes from the very literal “north face” of a mountain

in the northern hemisphere; the coldest, most formidable route for any professional mountain climber — an apt metaphor

for the challenges we have to overcome in our lives. With decades of cultural legacy packed into their wares, one

fleece jacket has risen above the rest as The North Face’s most iconic garment: the Denali.

First launched on the backs of Todd Skinner and Paul Piana in 1988, the mid-weight jacket was the perfect

layering piece for the climbers as they took on the Salathé Wall expedition. Now, 31 years later, The North

Face has jumped through time to stitch together the ‘95 Denali. All the defining traits of the jacket are

intact, from the high pile fabric to the woven overlay, but for this iteration, they’ve combined the jacket’s

long legacy with a chilled out, mid-90s vibe.

Ever since its debut on the backs of Todd Skinner and Paul Piana in 1988 as the daredevil duo did their first

free ascent of the Salathe Wall in Yosemite, the Denali has more than earned the title of the “forever

fleece” and transcended mountaineering to become a streetwear staple. Now, 31 years after its debut,

The North Face has jumped through time for a Denali jacket stitched with the spirit of the 90s, while

maintaining technically intricate details like high pile fabric and woven overlay.

Like much of the ‘90s nostalgia boom, the best way to reinvent the past is by putting it in the hands of the

next generation of groundbreaking artists charting new paths in their explorations of identity. And what better

way to embody the ethos of modern exploration than two artists climbing their own peaks of creativity? For the

reissue of their 90s-era Denali silhouette, The North Face traded snowy vistas for London’s urban sprawl and

brought together Jess Young and Kai-Isaiah Jamal to talk about their trailblazing explorations of identity,

how they began in their respective artistic fields, and what comes next.

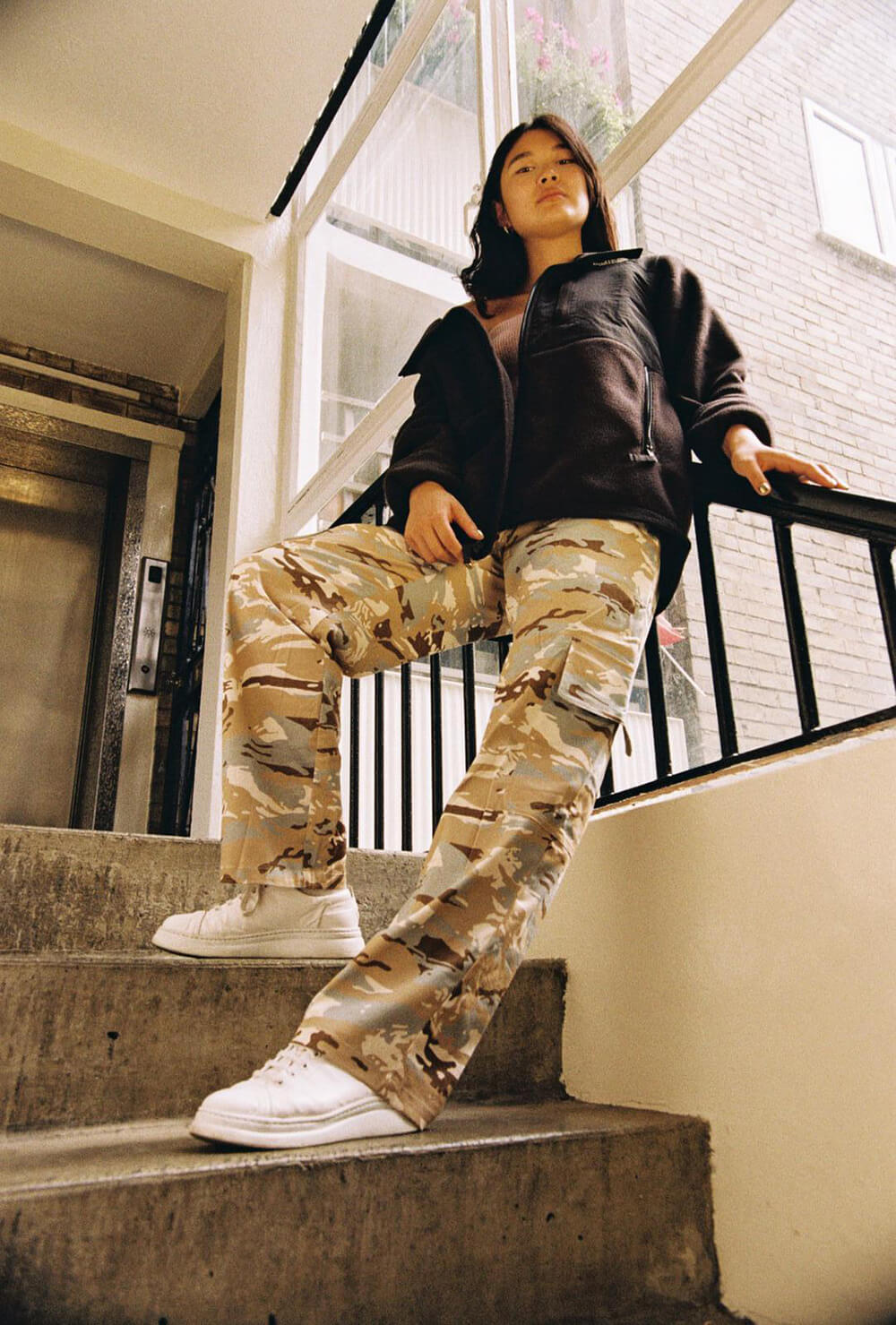

Jess and Kai: The Artists Exploring the Depths of Gender and Sexuality

Jess Young: Painting away toxic masculinity one nail at a time

How long have you been a nail artist?

I’ve been a nail artist for a total of five years now, but I’ve been doing nails since I was really young.

I remember being at primary school and having my friends over after school and giving them manicures.

But I think what started the interest is that my mom would go to a lot of her friends’ nail salons

and I’d follow her around. I really wanted to try it out on my own so after she’d get her nails done,

she’d take me to the nail supply store two doors down. I’d fill up my kit, watch YouTube tutorials,

and learned how to do nail art. I think doing art all through school helped me find my own artistic

style. It all went hand-in-and from that, and then when I started college, I had just turned 17

[and] started working at WAH Nails. That’s where everything set off and I met the right people

and got the right experience.

Tell me about how you came up with the idea for Boys in Polish.

It was during my art foundation two years ago. At the time, I was doing a fashion foundation. There were two boys

who were wearing nail polish and I found it really interesting. I’d never really seen boys wear nail polish b

efore, so just seeing that made me realize that guys need to be more open and express themselves in different ways.

I loved it. Why can’t guys do this more and embrace more areas of themselves?

That summer, in 2017, I decided to [photograph] my guy friends wearing nail polish as an initial visual concept,

just to put the idea out there and say, “Look, you know guys can wear polish too.” It got really good feedback

and everyone loved the idea, and that’s when I decided to keep it as an ongoing series. I think what guys

resonated with the most was that they could talk about issues that they wouldn’t usually talk about because

getting your nails done is such an intimate process. I’ve got your hands, you don’t have your hands to

make a wall, to scroll through your phone or distract yourself. So you really have to speak what’s on

your mind. It became a platform for guys to speak about toxic masculinity and the struggles that they

have being a man, and what’s really on their mind.

With the project, do you have a particular story that has stuck with you?

Yeah, definitely. I’ve painted my nephew. He’s only just turned four, but I think it’s important to

teach the next generation about being more open and expressing themselves because I feel like men don’t

have the courage to do that as much. When I shot my nephew for the project, he asked for Hulk and

Spider-Man. I thought it was really sweet because after doing his nails, my sister messaged me the

next day saying, “Oh, when Mason went into nursery all the girls loved his nails, and the next day

they all came in with painted nails because they liked Mason’s nails.” That is really cute because

you don’t expect it to be a reversed role like that. He loves getting his nails painted and even when

people say things to him at school, he doesn’t care.

“It became a platform for guys to speak about toxic masculinity and the struggles that they have being a man.”

– Jess Young

What challenges have you faced along the way that have shaped who you are?

The challenge came when touching more traditional masculinity. Straight guys were less open to the idea,

so I had to think of a way to ease them in.

What ideas did you come up with to ease them in?

I think the beautiful thing about being a nail artist is that it opens the door so much to what you can

actually do. Obviously, with nail polish, it’s just a color, but when you’re a nail artist you can

paint anything, it’s literally art on a nail, the same way you would get a tattoo. So I had to think

along those lines and be like, I need to make sure that whatever I paint on these guys’ nails is

something that they’re going to keep, and it’s 100% their vibe.

I want to be free to shoot all kinds of masculinities. I’ve actually learned a lot. I’ve seen different

walks of life, different personalities, expressions. So it’s actually broadened me as a nail artist,

and the way I work. But I think that’s an important thing; making sure that when I can shoot the guys

they’re comfortable, they get to pick their location, what they have on their nails, and what they

wear. Learning how to adapt to these masculinity tropes.

Guys tend to go for more negative-space designs; those designs where you can actually see the nail

and do a little painting on them, instead of color in the background. It’s funny how you have to

think about these things, you can’t go all out. And hopefully that will change soon, but I need

to take baby steps towards that.

I’m curious why you think such a simple action like nail painting can transmit such a powerful message?

I think it opens guys up. Guys will start to wear more makeup and are starting to be more adventurous

with their choice of clothing. It all ties in with the whole movement of guys being able to dress

more freely and actually be themselves. Obviously, for girls, it’s very easy for us to pamper

ourselves and get our nails done, get our hair done, and get a facial, but it’s not as easy for

guys to do that. Why? We’re all human and we all need to love ourselves.

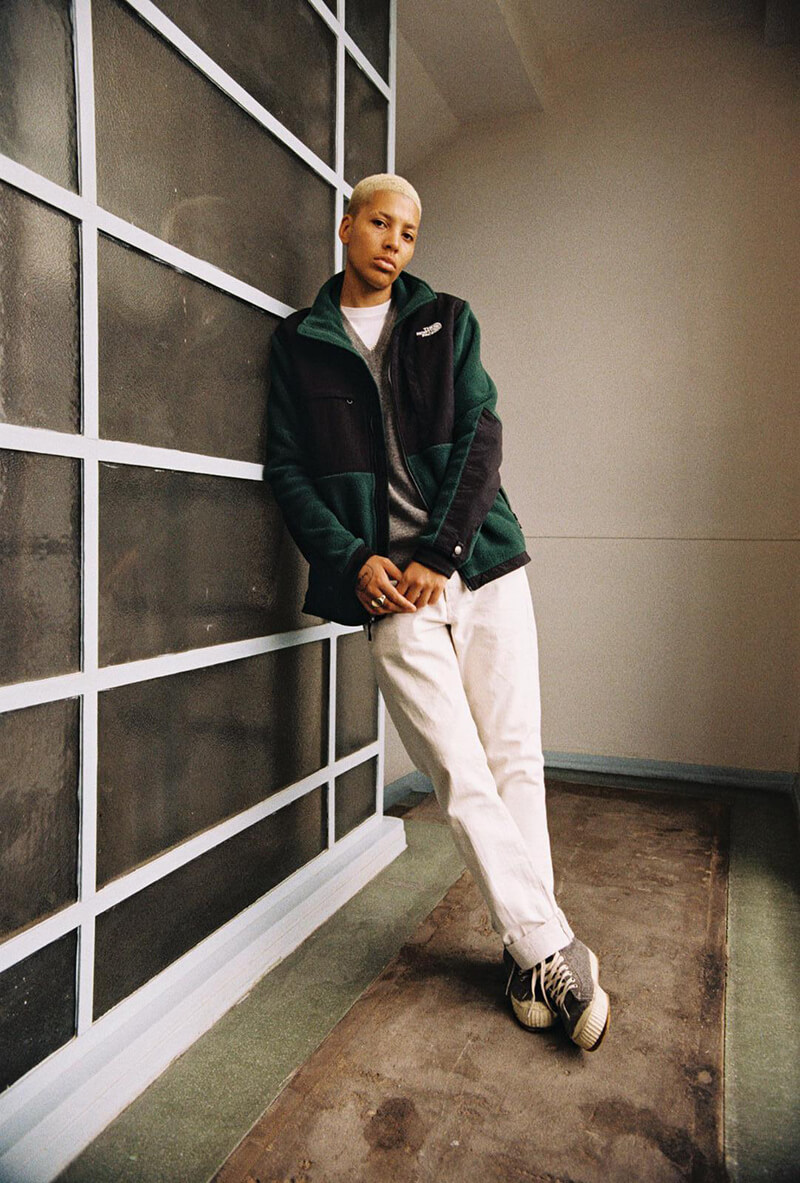

Kai-Isaiah Jamal: Bringing Black Queer Trans Visibility to Spoken Word Poetry

What sparked your interest in spoken word poetry?

A huge part of it was a way to access language; self-observation became something that was inherently co-existent

with my identity. Me coming to understand who I was and how I could present and how I could identify.

That was my first instance in being able to talk about it and being able to also live it to some extent.

Was there a spoken word artist that encouraged you to get into this form of poetry?

When I was growing up, I watched a lot of slam poetry. Slam poetry was the place that I saw Black, queer,

[and] trans voices in poetry because my first access to poetry was all the romantics. It was John Keats

and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. These white, cis, men. That was it.

I feel like a lot of spoken word poetry is seen as a bit angry because there’s so much emotion in it.

That anger is good. There are so many situations and so many poems that have been a reaction that

I’ve had to an experience with somebody and really felt uncomfortable, or even just a little bit pissed off.

It becomes a medium in which I can healthily address that. And it also gives you a moment of processing.

A lot of mine is about conversations that were difficult to have with people. Often regarding my sexuality

or my gender or my identity. It almost became this one-sided conversation. I wasn’t asking for a response.

That’s important but I also make really tender work. A lot of it is a cathartic process that gives me a

space to be vulnerable and be tender and soft, as well as more assertive, angry, aggressive, work.

They both mirror each other and reflect how I’m feeling at the time.

Yeah and that takes away the anger you might harbor in real life or in your day to day and gives you an outlet. That way you’re not yelling at everyone all the time.

Yeah, exactly. A situation happened and then I have a moment to process it and turn it into something that is more

articulate. There are so many times where we respond instantly because that anger is present.

Whereas when you actually have a moment to reflect on it and find a different way to speak about it,

I find that a healing process.

You’re in the artist collective BBZ. How does being among this creative group help you elevate your craft?

It really gives me a driving force because we are all from certain demographics, which means that there’s no judgment.

Also, just to be around other queer, people of color, and especially Black people of color who are creative and who

have similar lived experiences as you. It’s a blessing to be in a collective.

How did you get into the BBZ collective?

So I first saw the founders on stage at UK Black Pride and just observed what they were doing from a sideline position.

And one day I sent them some work and was like “What do you think of this?” And then I shared a panel with

Travis Alabanza, Chloe Filani, and Munroe Bergdorf [for the BBZ x Tate Exchange panel] and it just took off

from there. We realized that we had this common ground and they invited me into the family. That was it, really.

What challenges have you faced along the way in shaping who you are?

There’s definitely been resistance obviously when I came out. Not all friends and family supported it or necessarily

understood it, so that was a massive challenge; having to really understand what it means to take yourself first.

For such a long time, I was prioritizing everyone else’s feelings and emotions and ideas of myself. We live in a time

where everyone talks about self-love and self-care and really pushing up past a hashtag. A huge part of my practice

was being able to set boundaries; whenever you set boundaries you’re going to face an obstacle because it makes

people feel uncomfortable, but it makes you feel comfortable. Just existing as a queer trans man of color is a

massive challenge, whether that’s healthcare systems, whether that’s societal pressures, whether that’s body

image. There’s just so much that is enlaced in somebody devaluing your identity or questioning it.

We live in a time where just trying to have enough time and money to work on yourself and look after

yourself and be kind to yourself isn’t something that you can do — it’s not feasible and attainable 24/7.

How you’ve seen access to the arts change for London’s POC and LGBTQI communities?

There has been a massive shift. There are more queer or LGBTI+ people in the arts who look visible.

For such a long time, our voices have been censored or erased or monopolized or made into this tokenized

standpoint in the community. I’ve seen, especially with my generation, the idea of people just wanting to do things;

instead of working with an institution, so many people are making their own exhibitions and art collectives.

Doing takeovers of these massive institutions and turning them into something that is solely by them and for them.

That’s been a massive shift.

We still have a lot of work to do in terms of the way that we receive work — especially from people of color.

It’s often an incessantly supposed to be explicitly Black or Brown or Afrocentric in this one narrative.

We need to push past that and look at the idea of Black art existing because the artist is Black as

opposed to because they are making the work that is in resistance to something — or making work that

is palatable or digestible by somebody else. Of course, the art scene has been dominated by white, cis,

guys for a long time. It’s about completely diversifying the institutions, as well. So as opposed to

always having a governing body that fits that section of society, having other people with a completely

different perception and perspective. It gives access to the people who maybe aren’t as privileged as others.

“For such a long time, our voices have been censored or erased or monopolized or made into this tokenized standpoint in the community.”

– Kai-Isaiah JamalThe Fluidity and Freedom of Exploration

What does exploration mean to both of you personally?

Kai:

I feel like my transition especially has been a huge exploration. Not a lot of people have the

opportunity to reintroduce themselves at a later age. I was 18 when I came out, so it was almost like I

was this fully formed adult who then had to relearn myself, unlearn my old mentality, and then reintroduce

myself to people. That was a huge exploration for me; exploring masculinity outside of a position that’s

normative and almost studying it. Having to really look at how I could reimagine or redefine my masculinity

so it still felt authentic to myself. A huge part of that was exploring and kind of like trial and error.

Exploration is this journey and this journey exists in me. Every day, I would learn something new about myself

and it isn’t this A-to-B linear thing that I’ve thought it was going to be.

Jess:

Knowing your passions and following your heart. I used to have very extrinsic values in the sense that

I was around the wrong kind of people who wanted to be famous, and wanted to wear nice clothes, wanted

to hang out with cool people. Being around that environment, you absorb that energy, and you become that,

right? So when I dropped out of uni, I had to take time out for myself and [decide] what actually works with me.

That’s when I come up with these more intrinsic things, really find my purpose in life. You know, get to know

myself better, and what I actually stand for.

As corny as it sounds I actually started to read a lot more, I went to the park on my own, I meditated,

all of that. It does help. I think in terms of aspiration, [making] sure that you’re doing something

that you believe in and not necessarily pleasing a crowd of other people because otherwise, you’re living a lie.

It’s such an inward journey. You need to really look into yourself and be happy with who you are, that’s like the main thing.

How has London helped you explore your creative process?

Jess:

I think being at WAH, I see different walks of life, but the people that always stuck with me were my WAH family.

The girls I’ve worked with for five years, they are my family. They are a community, and a sisterhood to me, so I’m

very grateful for the whole experience and journey. Even though WAH is closing, it’s not a sad thing because I

know we’re all growing together; we’re moving onto bigger things, which is really nice.

They’ve seen me break from that extrinsic mindset to the intrinsic, and the fact that they stayed along for that

journey means that they’re my soul-sisters, you know? They’ve accepted every piece of me, and I think that’s what

makes them so special to me.

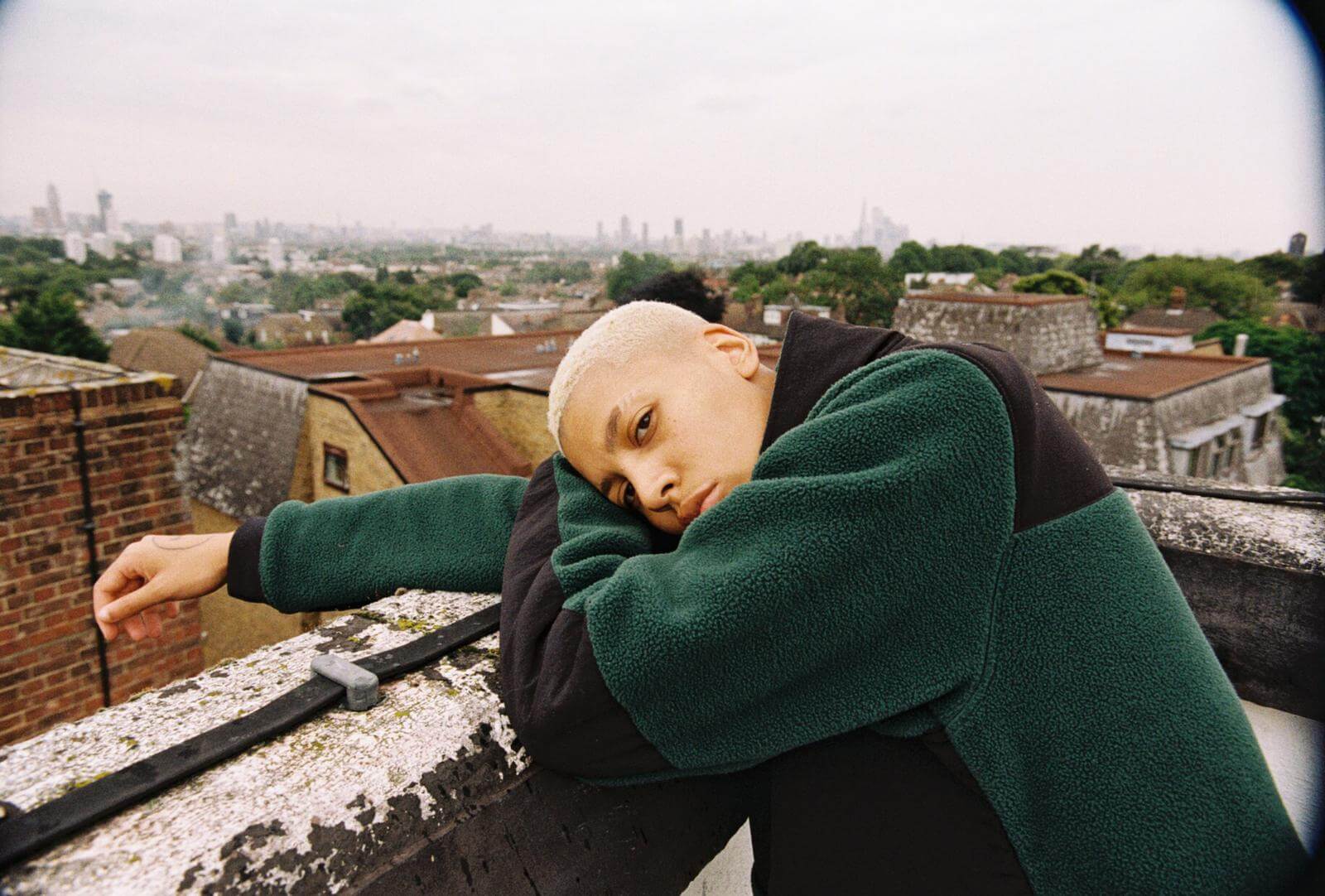

Kai:

It’s not until I’m out of London that I realize how fortunate I am to have it. London helps in the sense that there

is quite a lot of fluidity. There’s a lot of chances to be able to self-identify and learn new vocabulary and

new mediums and meet new people. It’s a very busy place where you exist amongst so many people. I’ll go to an

event and meet someone and there’s always some sort of connection that’s there, whether that’s a creative work

that we can do together or just the fact that we’re in this space together.

There is a freedom here and we are very privileged to have that freedom. Who I am, what I write about, and how I write,

will it be received in the same way [in other places]?

“You need to really look into yourself and be happy with who you are, that's like the main thing.”

– Jess YoungBeyond Spoken Word and Nail Art: Looking Towards the Future of Creative Exploration

What do you want to explore about yourself and your creative process that you haven’t had a

chance to yet?

Jess:

I’ve actually got into doing music again because that was a massive passion of mine when I was in secondary school.

But I dropped it out of lack of confidence, and insecurity. But when I picture what I’m actually living for, I

want to make music. I need to do what I want to do and not give a shit about what other people think.

I’ve begun to explore that more and really find my sound. [Music is] a really good way of expressing myself emotionally.

Now I have a more healthy outlet of expressing my feelings and emotions, and I think that’s why I encourage boys to

explore themselves and what they resonate with creatively. Because there are healthier outlets, you know?

Kai:

I was thinking about this the other day. Where do I want to go with this and what’s the next step?

I really want to create a production, like a theater production, which is a medium that I don’t have necessarily

the best expertise in. But I would really like to narrate a poem in the form of a play. That’s the next step,

which is scary because I have no previous knowledge or experience in it, but [I have] the same feeling I had about

poetry and trying to make it an accessible space for working-class, queer black voices. I wanted to try to have that

impact in the theater world and just make theater spaces accessible.

Growing up, I had this incredible opportunity at school to be able to go and see all of these plays and productions

as part of this [program] to get young people into performing arts. I had this incredible opportunity to go see all

of these plays and realized that there were certainly people at my school who had never been to the theater before

because it doesn’t feel like a space for young people or working-class people or queer trans black people. It began

as a middle-class white space so that’s definitely the next venture and something that I really want to explore further.

Underground theater, like community theater, can be such an interesting space to shoot off ideas

Kai:

Yeah. 100%. And making that affordable. Because that’s where it is, and that’s a huge part of what I want to be able to do.

If we’re looking at impact and a guarantee of something, I want to make spaces that were once not accessible for people

like me, more accessible for people like me.

“…being able to connect with one another and having time to be in one another’s company is really important to [our] safety and well being.”

– Kai-Isaiah Jamal

What message do you want to convey through your work?

Jess:

Self-love and acceptance, and not being scared of the world.

And Kai, what do you want to communicate to other queer black trans men?

Kai:

We are here. Even if it feels like we’re not, and even if it feels like we’re super invisible and unseen and erased,

we are here. But also that there are so many narratives to our experience that aren’t solely this linear or one-dimensional thing.

There are so many people and so many types of people that can all exist [and] have a collective lived experience.

Just being able to connect with one another and having time to be in one another’s company is really important to [our]

safety and well being. We need to stop making work for other people and start making work together because only we can

represent ourselves how we want to, and we don’t have that full creative control all the time. It’s something we really

need to display.

- Talent: Jess Young

- Talent: Kai Isaiah Jamal

- Director / Photographer: Blue Laybourne

- Gaffer: Austin Philips

- Assistant: Lemarl

- Stylist: Sophie Casha

- Style Director: Atip W

- Creative: Josh Wilson

- Producer: Indigo Janka